The Making of Kenya, the documentary film.

The Making of Kenya, the documentary film.

The story that took 3 years to retell.

Backstory

Being a part of a Christian humanitarian organization, I've had the priviledge to travel abroad. My background is in film production, but short of bringing a camera on these trips, the two worlds have never really intersected.

In 2000, a team from my organization (RCCM) traveled to Zambia and the over 20 hours of video I captured there turned into a short documentary film. Now, 6 years and three documentary films later, documenting these trips have become a central part of what I do. The trips are not about the films -- the trips are about touching and helping people. Offering hope to the hopeless. I quickly realized how powerful these experiences were and that they should be documented. We produce these documentaries for two reasons, 1) to creatively document our impact and 2) to document and preserve the culture, ways, and beauty of these foreign lands.

Our first three films, Zambia, Napoli, and Huts of Refuge have experienced surprising distribution success and have added notoriety to what we accomplish overseas.

Our fourth film, Kenya, represents a major advance in production quality and value that we put on these films. Months of planning went into the pre-production of this film. Our equipment list and crew is much more complete. We also have a budget (wow). One thing that has not changed is our methodology.......... As we travel to Kenya, it will be our first time there. Besides our hosts, we do not know anyone there nor do we know the specifics of our schedule. We feel, as with our past films, that this will give us a fresh perspective and an open-minded approach to the experience. We have no scripts, planned interviews or locations. We have no idea what to expect. We do know that the primary cities will be visiting are Mombasa, Nairobi, and Eldoret. During our third week in Africa, we will be in Harare, Zimbabwe. A travel advisory was issued by the US government warning travelers to avoid Kenya because of suspected Al Qaeda activity there. The US embassy will be closed. We'll see how this might fit into the film.

Preparation:

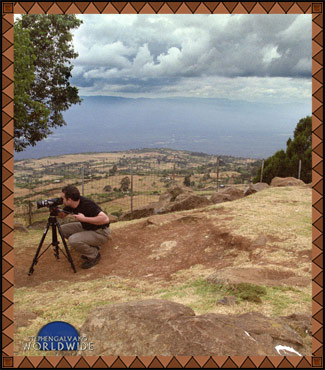

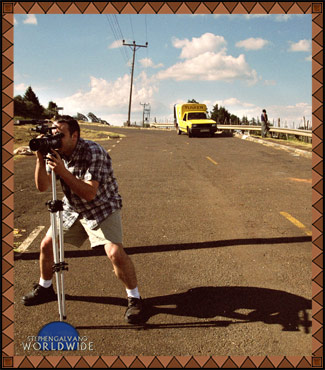

When deciding what equipment to bring, there are a number of things to consider. We would love to use a complete film package and do justice to the many telling physical and social panaramas we are sure to witness, but we need to be un-noticable, or at least unobtrusive so we can capture stories without changing the essence of them. Many natives, especially those in remote locations have little exposure to cameras. To authentically capture them is tricky. We do many shots of candid conversation, telling shots of natives in everyday life, shots in tight vehicles, and shots in places where we probably shouldn't be. We always try not to look like filmmakers....more like tourists. If we look innocent enough, we can usually get away with getting something in the can from locations such as foreign diplomatic areas, airports, and other sensitive areas....before getting kicked out.

Our primary criteria is to have a camera that is as small and innocent-looking as possible. We do travel with a rather full equipment list such as steadicam, jib arms, camera support, lens options, and full external audio devices. Although we do use this equipment for cut-aways such as wild life and establishing shots, we almost never use it otherwise. The bulk of our film will come from having a small camcorder at our hip and rolling a ton. As a result, many unique stories will be collected. I'm rather convinced that the same will hold true while capturing situations in cities and small towns anywhere. There are interesting stories all around us, and with creativity and patience in the editing room, these stories can become captivating films.

The name of our company in New York is Colors Studios. The production division that handles these documentaries is called Mwanga il Uliwanya which means light of the world in Swahili. That is a common name for Christ -- which is a central part of our message overseas. The name's double meaning is based on our filmmaking methodology. We pride ourselves on not embellishing these films, genuinely retelling experiences, no retakes or staged shots and using only available light -- usually sunlight. Hence, light of the world.

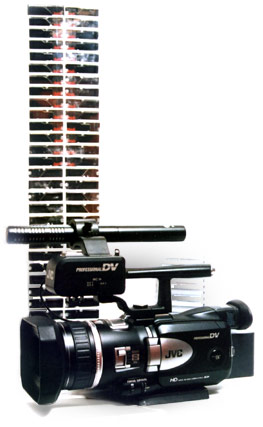

As mentioned above, the cameras we will use is always a debate. The primary consideration for our camera is size. That eliminates our ENG and film cameras that would traditionally offer a better look than a consumer camcorder. JVC has just released the world's first small 720p camcorder. We at Colors like to stay on the cutting edge and that has gotten us into trouble in the past and it may here as well. The HDV revolution is going to be a very good one for us. The immediate problem with HDV is that it is not yet supported by the major editing platforms. I got word from a friend at Apple that they have "just now begun" to think about how they may support HDV in future versions of FCP. With faith in Apple, and with no specific deadline for Kenya, we have contacted a long-time friend at JVC and we will have some of the first JVC JY-HD10U shipped to us ready for our late October departure date. We are excited by the prospect of shooting within our criteria -- in HD.

The JVC isn't perfect, nothing we've ever used for one of our documentaries is. Audiences tend to understand the nature of our films and accept that they may look different than a studio picture. In our minds, things such as a jitter from a handheld shot or a moment of focus loss adds to the authenticity of the film. Visual imperfection it is to be expected. We have taken some measures to reduce these types of artifacts. The genius rigger in our group has made....let's call them...devices....one will reduce camera jitter on handheld and moving vehicle shots. We also picked up a Steadicam jr.

The JVC shoots natively in 16:9, 30p and renders a flat, rather desaturated picture. This will work just fine for post-processing.

Audio is the single most important technical element of the production. Smooth, discernible audio is what gives a project professional production value. Audiences are quick to forgive poor, degraded, or heavily stylized visuals, but there is no better way to get an audience to tune out than having poor audio. A good example of this is one of my recent short films. I was very pleased with this project and was convinced that others would love it. After the presentation, person after person politely said that it wasn't my finest work. I was quite surprised by the reaction but learned an important lesson. Only one out of the many people I spoke to that night said they had a hard time understanding the dialogue. A few weeks later I went back and looked at the film with a few other filmmakers. They recommended that I remix the audio. The entire film was set to a rather loud soundtrack. I realized that I, as the director, had the dialouge memorized...but others may have a hard time understanding it. Long story short: I did not change one frame of video, but I entirely remixed the audio. I re-released the film nearly a year later to a new audience and they loved it. It was interesting that the first audience did'nt even know why they did'nt like it. Audio is the heartbeat of a project. If the audio is bad, the film will be received as such no matter how good the rest of it is.

That said, it is extremely difficult to capture good audio on a "run and gun" documentary. Our primary salvation is our very talented audio engineers who make even our worst audio mediocre. Even so, we have an extreme emphasis on capturing the best possible audio on the field. It is only because of this effort that can make bad audio usable. Although there are many areas we will improve on for Kenya, no one item is more important than capturing better audio. For Kenya, we will bring along Sennheiser ME66 shotgun mics, along with multiple AKG wireless systems that we use with Sennheiser MKE-2 lav mics. We will use a shotgun (mounted to the camera) for general capture, and a second mic, a lav, when we are tracking specific team members. Even at times when we are capturing from the lav mic, we will also be capturing from the shotgun on a separate channel which can be balanced or eliminated in the final mix. We use AKG 6100 and 8100 wireless systems in our studio. They are not made to be mobile, but they can be rigged to do so. For our last trip to Africa, our techs rigged up a compact, rechargeable 12v battery pack that lasted all day and was compatible with their funky voltage and outlet pin configuration for recharging. The wireless receiver fit in a side pouch and it connected to the camera via XLR. The AKG 8100 is a high-end UHF diversity system which has worked out great in the past and we never had a range issue. Many (even costly) ENG wireless systems we have used have not performed nearly as well. We also will bring along a portable Minidisc recorder. We're big fans of MD. We have been using them in our studios for years for demos, auditions, or anytime we need a quick, high-quality recording. They are versitile, and have been a perfect fit in our remote production packages. Whenever we have more than a few minutes to setup, we always record duplicate audio on MD. We also record ambient and foley on MD. While overseas, we host various gatherings from extremely large evangelistic-type crusades to more intimate gatherings with political officials and such. At these events, we have up to 8 channels of audio recording. Any production's audio quality is a vital element that must be well-thought out, well-captured, edited and engineered.

We survived.

November 2003

We're back from the trip to Kenya and Zimbabwe. It was a grueling 3 weeks of 18 hour days. We shot an amazing 80+ hours of HD footage. We also recorded over 110 hours of audio (dialouge and music). In all, we captured more than 10 hours of material per day totaling more than 200 hours of footage....that all needs to be logged and organized. Should be a fun year....... The trip was an amazing experience and far more rewarding than we ever imagined. Even having been to Africa before, our pre-conceived notions of what we might capture were thoroughly shattered. We got some really terrific stuff. My feeling is that Kenya will be the most socially conscience film that we've produced. We captured some unique stuff that will offer an insight into the social landscape of Kenya. We got the sunrise and sunset everyday and it seems everything in between. It was truly a life altering experience and my only hope is that the film will do as intended: Retell the essence of this experience. We have it in the can, it's all in the next step....... EDITING.

Logging.

January 2004

Logging and organizing: Unlike a narrative film we have no script to follow and there is no specific story line that will shape the film. We just have a bunch of raw material of day to day occurrences. Because of the sheer volume of material, it is vital that it all gets organized and logged so we can access it as needed. Over our past projects, we have become convinced that organization is the key to a successful documentary project. Again, if this was a narrative, we would know exactly how to piece it together -- the editing process would be finding the best takes and angles and assembling scenes as called for by the script. Documentaries are a much different beast. The story is shaped in the editing room. However you slice it (no pun...), a system of logging, organization and filing must be conceived so you can effectively manage and use the material. The only rule that will govern our editing of Kenya is chronology. For the sake of accurately re-telling the story, we are going to do it in order.

Logging and Editing Update.

(June 2006).

I thought I pass along our final material management process albeit a bit unwieldy: We had never before worked with such a mass of raw material, so I will admit that this process changed, and changed again during the project.

1) We did not watch the material too far ahead of where we were editing. We planned on watching and logging all the material before we started. After about two weeks of that we quickly modified our thinking for 2 reasons:

a) watching just short spurts of the footage gave us a clear direction of where we were going next without cluttering our minds with too much material. We never had a precise measurement of how much to watch in advance, but we watched enough to finish the sequence we were working on (for example, "end of day 14: nairobi slums") and the entire next sequence (example "day 15: sunrise/beachtrading") -- to conceive a transition to it. Depending on how detailed sequences or days (meaning a day in the film) were, we sometimes logged more. It usually worked out that we were logged 5-10 hours in advance. b) Watching hour after hour of raw footage was making us nauseous.

2) We used FCP's Bin filing system and logged material into bins named according to the reel number. For example, all logged material from tape (reel) number 9 was placed into a bin (or folder) named "09". This step is only recommended if you are cutting in chronological order.

3) Within each bin we had subfolders named after the sequences on that reel. In case you're wondering, "sequences" is what we called a combination of shots that came together to make a scene. For example, shots collected at the August 7th Memorial Park, where Al Qaeda bombed the former US embassy in 1998, was compiled into a sequence. The 8-hour van ride from Nairobi to Elodoret is an example of a longer sequence. So...

4)....Dividing the material into "Sequences" became our primary organization method.

Editing.

(September 5, 2005)

Two years after the introduction of the first HDV camera, FCP v5 was released.....so we can now edit HDV. In the meantime, many workarounds have been spread over message boards which have prevented a total stand-still in our new HDV room at Colors. These workarounds have been a bit cumbersome, but a worthwhile sacrifice to get HD resolution. With the volume of material we have for Kenya, we did not attempt an editing workaround as it would have added time-consuming steps to what was already going to be a tricky technical production. The workarounds have been helpful on a number of short films we have made in HDV in the meantime. Through these films, the promise of HDV was bright and we were producing them with little or no budget.

We started editing on a year-old G5 machine that had previously been our After Effects computer. In the days immediately after FCPv5 was released, users began complaining of a lag in responsiveness while editing HDV when compared to the very responsive nature of DV. After experiencing this "HDV lag" we quickly purchased a new, more powerful machine that would hopefully make editing HDV smoother. My friend at Apple highly recommended the "best video card you can afford" and secondly, of course, maxxing out the RAM. When we received the new computer we were surprised at the difference in performance. From that point through the intensive year of finishing Kenya, the technical side of the production was a breeze. The creative was not.

Having so much material was a double edged sword. In general, we usually felt like we had enough footage for a particular sequence to tell a compelling story, but because there was so much footage, much had to be cut. That was heartbreaking. We look forward to including much more material on the DVD as Extras, Deleted Scenes, and Menus. We probably will do the same, or more, online. We did miss some shots. I'll never forget a magical moment that I missed while grabbing batteries. It's bazaar how that's what you remember. It does lessen the pain when you review the footage and see great shots that you got....but forgot.

I have been working closely with the kind folks at Red Giant Software since 2002. Magic Bullet Suite has been a great finishing application at its price point and it continues to be for HDV. Because of our history with them, we knew all along that we were going to use Magic Bullet for finishing Kenya. Because the cameras we used for Kenya shot natively in 30p, we decided to leave the motion native and not use Magic Bullet Suite's Frame Converter to convert the FPS. Incidentally, we have used this converter with great success on 2 previous feature documentaries that were shot in 60i. Because of the new advances in the Look Suite and the addition of MisFire, we purchased the new Magic Bullet Editors program (this is the new Magic Bullet Suite minus the frame convertor.) I wish I could give a long and detailed account of this process, but in reality it was a piece of cake.

The Look Suite in Editors has a bunch of presets that mimic film stocks and looks seen in various films. In my opinion, the presets are a bit over-the-top, but they are a great starting point to get to the look you're going for. The Look Suite is a series of controls such as gamma, post saturation, filters, and others that come together to form your look. The presets are simply different combinations of these values. We have been thinking about the final look for Kenya since we started editing. We wanted more than just a film look. We wanted the coloring to be a creative element that would help tell the story. Magic Bullet worked wonderfully with this concept. Magic Bullet doesn't strive to look like film as much as it strives to be a toolkit to creatively impact the look of a project. We wanted the final output of Kenya to look like the story we were telling about Kenya - dark, colorful, contrasty. With a bunch of tweeking and testing, we were able to achieve the look we wanted with Magic Bullet. That look was applied project-wide. We also added some sequence-specific looks which we applied to individual sequences. What we like most about Magic Bullet is that it never sacrifices detail to achieve a look. In our custom preset, there is a small amount of "white filter" which I think looks alot like an optical Promist filter. This filter basically exaggerates the highlights and slightly blows them out. The Magic Bullet application does this without compromising detail.

It is quite remarkable that it resembles how it might look if it was done optically. I've included an example below. There are other parts of the Magic Bullet Suite that make it a compelling buy for any filmmaker.

Shot from raw footage (half resolution)

Same frame treated with Magic Bullet (half resolution)

The 1st cut....

....Always the toughest step for me. This is the step where the story is formed from the raw footage. It is creatively intensive and therefore very draining. I sometimes found it difficult to get into the flow.....there were days when I just couldn't engage. On those days, I usually got ahead on my logging. Towards the end of the 1st cut, a change in venue also helped me. After feeling confined in my studio for months, I ended up editing a good deal of the 1st cut in other places. I got to know the campus at RCCM wel....lugging my computer into rooms I've hardly been in. Sequences were grouped onto portable drives, so I could also just plug the drive into another Mac with FCP and a reasonable amount of power.

I tend to flow better at night. There were many days that I felt that I couldn't get started.....only to have a burst of energy late at night leading to a very productive number of hours. There are two 24-hour coffee shops within a mile of my studio. I'd often make runs all through the night to let off creative steam, for a quick change in environment, and of course, a large coffee.

It was important for me to be fully focused during this period. Being totally enveloped in the project allowed a greater connection and a more powerful creative flow. It wasn't uncommon for me to wake up with an inspiration or to even dream about a sequence. During the 3 months of the Kenya 1st cut, I did nothing else besides It, and the other essentials neccesary to keep a pulse. Mental and physical burn-outs were competing with one another and one would win every 15-20 days. I would then separate myself from the project...and sleep. It was amazing how ready I was to go back after that. During this process, I logged the most significant hours per day, averaging between 16 and 20.

This process should drain you. It is the process in which a documentary film comes alive. I always relive the experience in my mind and then tell the story based on what I personally recall. The 1st cut of a documentary is never something that should be scheduled or deadlined. It should be completed as it comes. Putting an expectation on a day or week such as cutting "15 minutes" is not effective on such a project because while it can be done -- you simply cannot be true to the story if you rush or plan the creative experience. For me, it's always difficult to begin cutting a new sequence. Every sequence you create is like a painter's first stroke on the canvas. The more you envelop yourself in the creative process, the more it will flow on a consistant basis. I found I had little downtime.

I usually need a trigger to get going. Usually my trigger is an inspiration I can recall from the raw footage. Inherit with capturing 80 hours of video is capturing some very amazing things. It is exciting to see a shot while watching the raws that astonishes you. It is an instant trigger and the sequence unfolds quickly right in front of you. That said, some of my favorite sequences in Kenya didn't have such a trigger. I just had to grind away with the raws. Eventually, inspiration hit me and the sequence got developed. Even though this process may not always be enjoyable, it is very rewarding. This was indeed the 1st cut. I purposefully did not refine the cuts and sequences in this phase, I merely shaped the story. I left refining for the next phase which would require less inspiration, but a more keen eye for detail....for which I wasn't zoned for in this phase.

Kenya ended up using a total of four 250 gig drives. "Drive A" contained roughly the first half of the captured raws, "Drive B" is a copy of "Drive A". The same is true with the second half on Drives C and D. Drives A and C were my working drives and were portable so I could lug them home or to different locations as described above. Drives B & D were internal SATA drives that remained in my main computer while I was editing that half. For security purposes, the drives were always separated when not in use. I also backed-up the project files across the drives and on a third drive on our external server. The final FCP project file for Kenya was just under 100mgs. Drives that are not in use or archived drives at Colors Studios are always kept in a fire-proof safe for added security.

2nd Cut, Audio Processing, and Final Cut

The 2nd cut is a welcomed phase after the grueling 1st cut. It's much more enjoyable as you watch and tweek rough sequences. Although for me it is always more than just a simple tweek, it still requires far less draining brainpower. This is the process that make my films more watchable. I balance out the emotion of reliving the experience, with the reality of the viewing experience and what would keep a viewer interested. It does water-down some of the passion put into the 1st cut.

I also refine transitions between sequences, experiment and add special-effects coloring, and even change some sequence placement.

This is also where we start paying close attention to audio. The audio ended up being as good as expected on the raws. Right after the 1st cut, we met with our audio engineer for the first time. His initial reaction was the same as always : "you need me along with a boom on your next project". We watched the film together and then started working on it clip by clip, sequence by sequence. Each and every frame of audio was edited in one way or another. Straight-forward effects such as EQ, and noise-reduction were done using Soundtrack Pro-- right off the FCP timeline. The more intensive effects such as imaging, stereo effects, reverb and other special effects were set via gigabit ethernet to an audio-optimized machine were the effects were completed and later sent back to the FCP timeline. As I mentioned near the opening of this article, discernible audio is vital to a project. In all, we spent nearly the same collective hours editing the audio of Kenya as we did the 1st cut of video. It's that important. One final note on audio: As I described above, the audio collected even with good equipment on a documentary can be horrific. A good de-noiser can be the most valuable audio tool one can have. The standard de-noiser that comes with Soundtrack Pro is the best that I've heard. Virtually all of the audio in Kenya was treated with some measure of this effect.

After we finished the audio treatment and the 2nd cut, I went through individual sequences a few more times and tightened it up further. After taking a week off to gain some objectivity, I trimmed again. A total of 16mins (about 15%) was trimmed from the film during the 2nd cut.

After the 2nd Cut, I screened the project for myself and a few friends and colleagues on the big screen in the beautiful RCCM theater. I took alot from that and then did a final cut during which I added the final color treatment (Magic Bullet).

Kenya was in the can.

Making a documentary film is always a labor of love. it requires an impractical amount of time, but when finished it can be very fulfilling. There is no better way to immortalize a story. I invite you to see the trailer and website for Kenya on the web at colorsstudios.com/kenya. The film in its entirety is now posted at SGWW.org.

Regards,

Steven Galvano